Many people reaching retirement age: How are local authorities preparing for the baby boomers?

Born between 1955 and 1969, they are now gradually reaching retirement age: the baby boomers. As this group accounts for a fifth or even a quarter of the population, local authorities are facing a major upheaval. Suddenly, thousands – and tens of thousands in cities will no longer drive to work in the morning as they did in previous decades, but will stay at home instead. Most of them are still fit and have plenty of time, as well as special needs and interests. As they grow older, health problems will increasingly arise. Some baby boomers will become seriously impaired. How can local authorities prepare for the retirement of so many people? How must they reorganize, create age-appropriate housing and adapt local amenities and leisure activities to the changing population structure?

Data instead of gut feeling

Since 2021, experts from urban sociology, spatial planning, geography, economics, mathematics, visualization, software development and artificial intelligence (AI) have been working with seven model municipalities as part of the interdisciplinary research project “Ageing Smart – Designing Spaces Intelligently” to develop an appropriate planning tool: software that combines AI and special mathematical methods. “The aim is to help municipalities make the right decisions based on data, rather than gut feeling,” says Annette Spellerberg, Professor of Urban and Regional Sociology. To cope with this demanding task, the decision support system requires a great deal of different data. This includes data about the baby boomers themselves, such as how many there are, where they live, what their needs are, and what this means for municipal services.

Ten scientists and their teams compiled the data for the baby boomer topography in the seven project municipalities. The municipalities represent three typical settlement areas. The urban area is represented by the cities of Kaiserslautern, Mannheim and Jena; the suburban area by the medium-sized centers of Nieder-Olm near Mainz and Remshalden near Stuttgart; and the rural area by Geisaer Land in Thuringia and the Palatinate municipality of Kusel-Altenglan. Of course, cities differ from rural areas.

However, Spellerberg emphasises that there are also differences between representatives of the same settlement area. In the Geisa region, which is located directly on the former German-German border, people have a strong sense of regional identity, which is not as prevalent in Kusel-Altenglan in the Palatinate. There are also differences between the cities. On the one hand, there is Kaiserslautern, which is relatively financially weak and has a high proportion of baby boomers. On the other hand, there is the young, science-oriented city of Jena.

The baby boomer types

Data collection was carried out in stages. Initial discussions with the municipalities took place in 2021, in which they described the local situation with regard to baby boomers. This was followed by a large-scale survey in 2022. In each model municipality, a representative sample of people aged 50 to 75 was taken from the population register. These individuals were contacted in writing, and those willing to participate completed a questionnaire either on paper or online. The questions covered topics such as daily routines, life situations, living arrangements, household types, choice of transport, leisure activities, lifestyle, quality of life and basic attitudes. "We had a good response rate of 25 per cent, covering around 3,100 baby boomers," said Spellerberg.

Based on the survey results, project partner the Fraunhofer Institute for Experimental Software Engineering (IESE) developed personas, dividing the baby boomers into three groups: domestic and thrifty (involved in volunteer work and church activities); family-oriented (for whom children and grandchildren are everything); and versatile and active (enjoying retirement and wanting to experience new things). IESE then held workshops with the local authorities to analyze their needs.

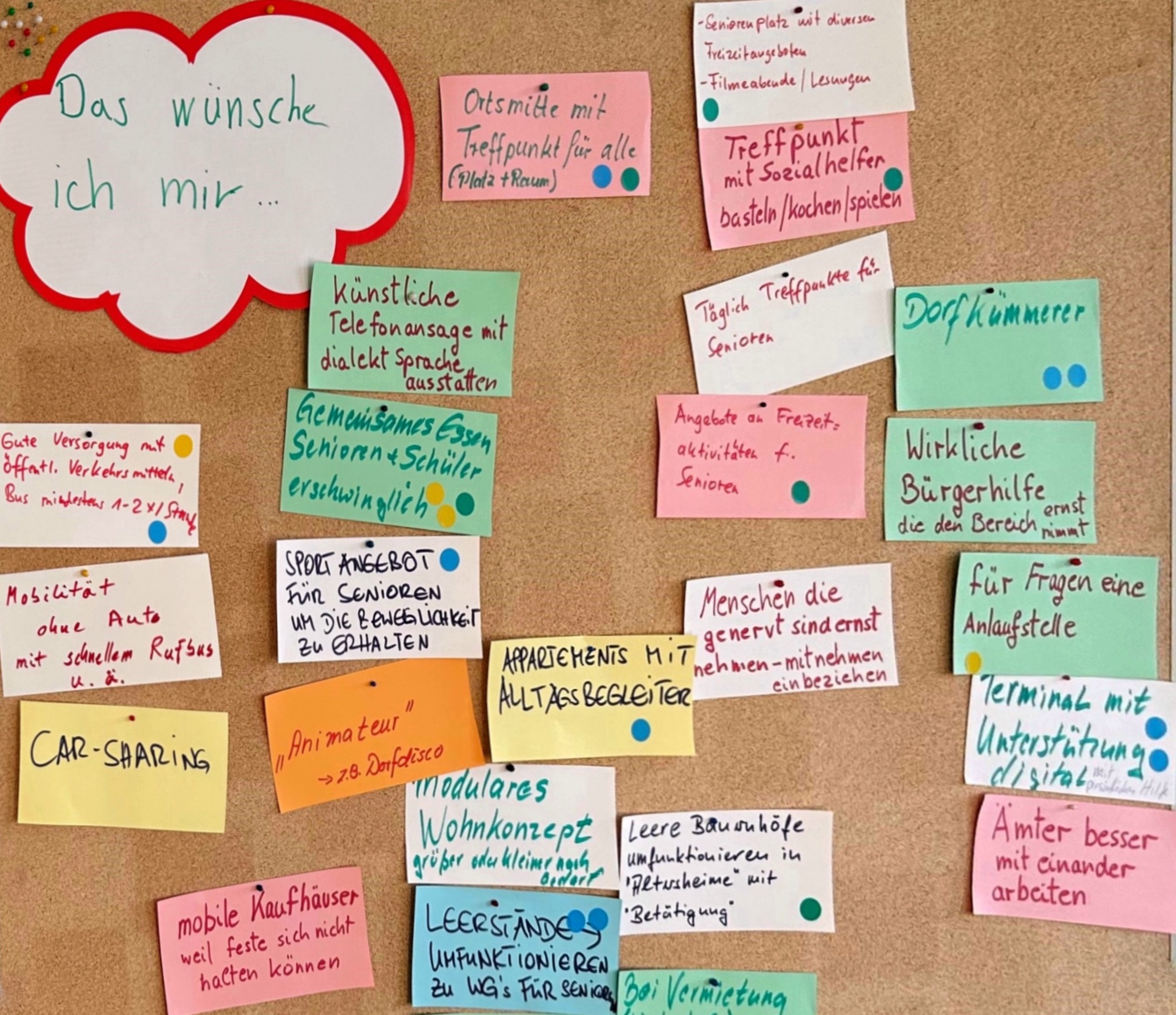

In other words, the local authorities were asked to specify what information they needed. For example, they wanted to know whether baby boomers live alone and how neighborhoods could be encouraged to prevent loneliness. The second main topic besides housing were public goods. The municipalities were interested in the local infrastructure that baby boomers need and want – for example, shopping facilities, doctors and leisure activities.

The accessibility feature

The project then entered its next phase, which focused on technical implementation. IESE set about programming the tool. Alongside the baby boomer data, information from the administrations of the seven model municipalities was incorporated, including resident data, data on building structures (e.g. apartment buildings, single-family homes, commercial areas and population density), public transport data and data on points of interest (e.g. town halls, libraries, sports fields, doctors and supermarkets). The Department of Digitalization, Visualization and Monitoring at RPTU was responsible for the visualization, while another project partner, the German Research Centre for Artificial Intelligence (DFKI), handled data management. The Department of Physical Geography at RPTU developed AI software in collaboration with DFKI.

The tool slowly took shape. The first features were created – functions that help with specific tasks. For instance, the mathematicians developed an accessibility feature – a model for solving everyday mobility problems. One task was to find the best location for new supply or leisure facilities, such as a library, community meeting place or medical center. The aim is to place these facilities in such a way that as many baby boomers as possible can access them quickly.

To achieve this, the profiles of baby boomers (including their places of residence and any physical disabilities) were merged with public transport and open street map, resulting in the completion of the optimization model. "It even takes into account the walking speeds of baby boomers," says Spellerberg. In Mannheim, the accessibility feature is already providing concrete assistance: the city is using it to determine the most suitable location for a new community center, ensuring that as many baby boomers as possible can reach it with minimal effort.

Is there a recreational area nearby?

Artificial intelligence has been incorporated into another feature: the green space feature. This was developed entirely within the Department of Physical Geography at RPTU. AI was given aerial photographs and satellite images of various model municipalities as training material, and it learned to distinguish green spaces from other types of land use. It also learned to recognize different types of vegetation – meadows, shrubs and trees – to distinguish between them and assign them different local climate effects. In other words, it can evaluate how well the vegetation in a particular location protects against summer heat stress. After many training sessions, the AI could evaluate neighborhoods, determining whether there were sufficient green spaces for people to relax in. The only thing left to do was to add the baby boomer data, and the feature was complete.

Sascha Henninger, a professor in the Department of Spatial and Environmental Planning, explains its intended use. “Many baby boomers are unable to travel for financial reasons, so they depend on recreational areas close to where they live. Our feature helps urban planners to monitor green infrastructure. For example, it shows whether there is a shortage of green spaces in neighborhoods with many baby boomers who are not so well off financially.” Urban planners can respond to this by designating areas as green spaces or by expanding public transport services, making it easier for baby boomers to reach green recreational areas a little further away by train or bus. The two model municipalities of Jena and Kaiserslautern intend to use the green space feature in urban planning in future.

Ground-level ozone formation

AI is also at work in the air hygiene feature, which Henningers' department developed in collaboration with DFKI. An AI system has learnt to recognize different tree species and categorize them into two groups: those that emit large quantities of isoprene, such as poplars and plane trees, and those that emit only trace amounts, such as apple trees and magnolias. Isoprenes are biogenic hydrocarbon compounds that form ground-level ozone when combined with nitrogen oxides found in car exhaust gases, for example. If there are many trees that emit high levels of isoprene on a busy road, pollution levels can be high. This poses a health risk, particularly to older people, as well as to allergy sufferers and asthmatics.

The air hygiene feature is designed to address this issue. It shows which streets may be affected by ozone pollution. "In future, local authorities can use this feature to help them make decisions, such as planting trees with lower isoprene emissions when planning new developments," says Henninger. However, existing trees should never be removed. One option would be to recommend ozone-free or less polluted routes to baby boomers.

Helping baby boomers to get fit is a financial challenge given the often-tight budgets of local authorities. However, the tool could be useful here, too, as it involves economists. They have created a municipal economic impact model that has been incorporated into the tool and which can simulate shifts in the age structure. If there are proportionally more baby boomers, there will be fewer workers available, but demand for doctors and outpatient facilities will increase. What impact will this have on finances? How can local authorities improve local care without placing too much strain on the budget? The tool's finance feature provides answers to these questions, offering another aid for decision-making.

Everything depends on the data

What was the outcome of the project after four years? “By combining the disciplines, we were able to create knowledge that did not exist before,” says Annette Spellerberg. However, implementation is proving more difficult than expected. It is therefore unclear what will happen after the project ends in 2026. A data-based tool requires a lot of high-quality, linkable and evaluable data. 'But smaller municipalities don't have that. They lack statistics departments and large databases. They lack personnel, expertise and financial resources.' The situation in e.g. Jena is completely different: the city has all the necessary resources and databases, and big plans for the tool. But what if other municipalities not involved in the project make enquiries? Spellerberg hopes that there will be follow-up projects. Collecting data on local baby boomers would not be a major problem. “But here, too, everything depends on the quality of the data. If the municipality making the request has insufficient data or poor-quality data, the DSS cannot be implemented.”

This is especially true since the data itself is not the only problem. Spellerberg's main conclusion from the project is that acquiring and compiling data is 'incredibly time-consuming', partly because there are no uniform data protection rules in the municipalities. Which data is processed and how? What is forwarded to which agency? Where and for how long is it stored? Everyone does it differently. Sometimes data was simply not available. Other times, contracts had to be drawn up for the use of specific data. Why is it so complicated? Sometimes, minor details prevent the data from interacting, which is precisely what the whole tool is based on.

Literature for a deeper dive:

Annette Spellerberg, Stefan Ruzika (2026): Ageing Smart - Digitale Instrumente im kommunalen Kontext: Daten, Analysen und Strategien (nicht nur) für Babyboomer (German language); Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden

Neumann, Ute; Spellerberg, Annette; Eichholz Lutz (2022): Veränderungen beim Wohnen und von Standortpräferenzen durch Homeoffice in der Covid19-Pandemie? (bilingual). In: Raumforschung und Raumordnung. Spatial Research and Planning. Doi: 10.14512/rur.133.

Spellerberg, A. (Hrsg.) (2018): Neue Wohnformen – gemeinschaftlich und genossenschaftlich. Erfolgsfaktoren im Entstehungsprozess gemeinschaftlichen Wohnens (German language); Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden

These topics might also interest you: